On November 11, 1954, Syuiti Mori turned out the lights on a small group of fruit flies. More than sixty years later, the descendents of those flies have adapted to life without light. These flies—a variety now known as “Dark-fly”—outcompete their light-loving cousins when they live together in constant darkness, according to research reported in the February issue of G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. This competitive difference allowed the researchers to re-play the evolution of Dark-fly and identify the genomic regions that contribute to its success in the dark.

“We hope understanding the genetics behind Dark-fly’s adaptations will shed light on how genes are selected during rapid evolution,” says study leader Naoyuki Fuse of Kyoto University. The Dark-fly project is the longest-running example of an experimental evolution study where scientists follow a population over many generations. It is also the first to analyze genome evolution in a multicellular organism adapted to a defined condition in the lab.

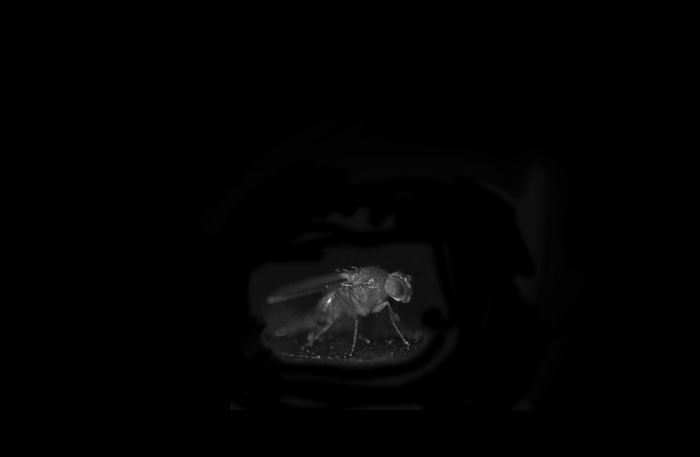

The project was initiated by Mori as part of a series of experiments investigating how the traits of fruit flies are altered in response to changes in their environment. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a heavily studied model organism often used to examine genetic changes during evolution. To keep the flies away from light, they are reared in vials kept in a large pot painted black on the inside and covered with a blackout cloth. When the vials and food need to be changed, the researchers tend to the flies in the pitch dark, then use a feeble red light to check on their work. Fruit flies can’t see this light because the species lacks those light receptor proteins that absorb red wavelengths.

When Mori retired, he passed on the precious fly stocks to his colleagues at Kyoto University, who have maintained them continuously to this day. The stock of flies has now spent more than 1,500 generations without light. In human terms, that would be like sequestering generations of our ancestors in the dark for 30,000 years.

Today, Dark-fly looks almost identical to normal (wild-type) D. melanogaster, but the variety is also subtly different. For example, Dark-fly individuals move around more in response to sudden light exposure, even after spending a generation in normal day/night cycles. They are also more sensitive to certain smells and have longer head bristles, which are sensory organs that serve as the fruit fly version of a cat’s whiskers. Dark-fly also produces more offspring when kept in constant darkness than in alternating light and dark.

But although Dark-fly does better in the dark than the light, is it more highly adapted than the wild-type to its dim environment? The team tested this hypothesis by housing the two types of fruit flies together, allowing them to mate at random, and then assessing the parentage of the flies that made up the next generations. The results showed that Dark-fly has a competitive advantage in reproduction over the wild-type when bred in the dark. Fuse suggests this might be due to differences in pheromone signaling when the flies select their mates, or to altered circadian rhythms of mating or sleep behaviors.

Which genes are responsible for the adaptation to dark conditions? Previously, the team sequenced the Dark-fly genome, identifying mutations that distinguish it from wild-type. But not many of those genetic variants are likely to be responsible for the adaptations that help Dark-fly thrive without light; many of the variants may have no effect, or may affect unrelated traits. To hone in on the dark-adaptation genes, the team performed another kind of experimental evolution study.

They first reared Dark-flies and normal flies in mixed colonies, allowing the two types to interbreed freely for 49 generations. These colonies were maintained in constant dark and compared to control colonies with normal 24-hour light/dark cycles. With each generation, those flies that produced the most offspring contributed more of their genes to the colony as a whole. As the genomes of the two types of fly mixed, those genes responsible for Dark-fly’s unique adaptations should become more common in the colony kept in the dark. To find those genes, the team sequenced the genomes of flies at the beginning and end of the experiment and looked for genetic variants originating in Dark-fly that became more common only under the dark conditions.

Such variants were located in 28 regions of the Dark-fly genome. From these regions, the researchers narrowed down the candidates to 84 genes. Among these candidates are likely the genes associated with dark-adaptive traits. These include genes that encode chemical receptors, and genes involved in pheromone synthesis, the formation of smell memories, and circadian rhythms. In future work, the team will examine the activity and functions of these candidates to link them to specific Dark-fly adaptations.

“We will soon have the ability to try my dream experiment: using genome-editing technology to introduce defined mutations into the wild-type to try to reproduce the Dark-fly’s traits. This would give us a precise molecular profile of this remarkable example of evolution in the lab,” says Fuse.

CITATION:

Dynamics of Dark-Fly Genome Under Environmental Selections

Minako Izutsu, Atsushi Toyoda, Asao Fujiyama, Kiyokazu Agata, and Naoyuki Fuse

G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics February 2016 6: 365-376; doi:10.1534/g3.115.023549

http://www.g3journal.org/content/6/2/365.full

Update added March 7, 2016:

We’ve since learned that GSA member and FlyBook Co-Editor-in-Chief Therese Markow pioneered related research in 1975. During her PhD, she showed the importance of genetic variation in movement towards light (phototaxis) for fitness in constant darkness or constant light. The project relied on a quantitative assay for phototactic behavior: the flies enter a maze where they make a series of 15 consecutive choices between moving towards or away from light. The more phototactic the fly, the more frequently it should choose the light. This allows not only classification of the trait along a spectrum, it provides a framework for systematically creating fly lines with extreme behavior via artificial selection – called “photopositive” and “photonegative” populations. Markow found that photopositive populations laid more eggs in constant light conditions and conversely that photonegative populations laid more eggs under constant darkness. In contrast, unselected flies were mostly unfazed by the light conditions, laying similar numbers of eggs in both cases. This showed that flies have the highest reproductive fitness in the conditions they are genetically programmed to prefer

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v258/n5537/abs/258712a0.html