Marnie Gelbart, Director of Programs at pgEd, shares her perspective on the need for bidirectional exchange between scientists and communities to shape the path forward. She pinpoints how interdisciplinary networks have helped pgEd grow and gives suggestions on how to get involved.

Marnie Gelbart, Director of Programs at pgEd, shares her perspective on the need for bidirectional exchange between scientists and communities to shape the path forward. She pinpoints how interdisciplinary networks have helped pgEd grow and gives suggestions on how to get involved.

In the Decoding Life series, we talk to geneticists with diverse career paths, tracing the many directions possible after research training. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee.

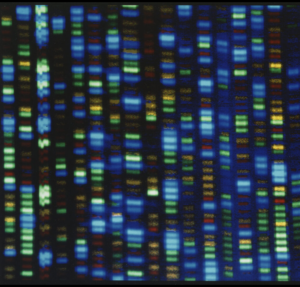

The Personal Genetics Education Project (pgEd) was established in 2006 to raise awareness about genetic technologies, as well as to address the related needs and concerns of individuals from all backgrounds and across different communities. pgEd advocates for transparent information sharing and two-way dialogue that is inclusive of all viewpoints. pgEd’s ultimate goal is to give individuals the confidence to ask questions and make informed decisions about whether and how to include these technologies in their own lives. pgEd’s efforts include creating lesson plans for middle/high school and college educators, organizing congressional briefings and conferences, consulting for television shows, partnering with faith leaders, engaging with library communities, and developing online tools and videos.

How did pgEd come about?

pgEd began in 2006 as a volunteer organization launched in the lab of pgEd Director Ting Wu, together with Jack Bateman and Dana Waring, in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School. It transformed with the help of departmental chair Cliff Tabin, who felt a responsibility for the department to engage with the public about exciting advances in genetics—as well as the surrounding ethical, legal, and social issues. With initial seed funding from the department, I became one of the first paid staffers. I collaborated with my colleagues, who brought backgrounds in education and social sciences, to build a curriculum for sparking conversation about genetics using accessible language. pgEd was primarily focused on educating through schools at the time; as we secured new sources of funding and expanded our staff, we’ve been able to branch out to different directions from there.

Over the past 12 years, pgEd has reached out to many communities and heard no shortage of viewpoints and opinions on genetics, ranging from unbridled enthusiasm to fear and mistrust. We’ve drawn strength from our interdisciplinary network of partners across research and academia, industry, government, Hollywood, and faith communities who have collectively helped us do better at building bridges and drawing more people into the dialogue. I think we’ll always continue to grow in how we work with these different sectors. Looking back, I never envisioned that I would be involved in such different strategies at pgEd.

Tell us about your journey towards becoming the Director of Programs at pgEd?

I was exposed to the rapid pace and direction of science during my postdoctoral research in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School. I was very excited to talk about the emerging advancements, and I particularly wanted to talk in an accessible way that resonated with non-scientists and make the information accessible. But “genetics” got personal for me when I was pregnant with my older daughter and went through carrier testing because of my ethnicity. I had so many questions, and I was fortunate to be very comfortable talking about these topics. These experiences were a big part of what brought me to pgEd, which gives people the opportunity to learn about genetic technologies and what may be offered to them and to feel comfortable asking questions.

What are the most inspirational and challenging aspects of your work?

The most inspirational aspect is the people that we’ve talked to who have shared their stories; I’ve learned so much from them. It is also very inspiring that there are so many scientists who are interested in getting involved beyond the bench. It has been such an enriching experience that has made me feel hopeful.

The most challenging aspect is not having enough hands to take on all the projects that we’d love be a part of. But we’ve been fortunate in how we’ve been able to grow over the years, and I’m looking forward to taking some big steps forward in the year ahead!

Being trained as a scientist, was it challenging to start conversations with non-scientists?

I was brought up as a traditional kind of academic—to the point that my father was a geneticist, my friends in graduate school were scientists, and I married a scientist. I don’t think I even realized how insular this was until I came to pgEd and heard a wealth of stories and experiences so different than my own. It had not occurred to me that my personal lens on genetics reflects, in part, how fortunate I’ve been in my life, whereas for people who have experienced a lot of discrimination, there is so much reason for mistrust.

As a scientist, I don’t think I was explicitly trained for the kind of engagement we do at pgEd—though there are many more opportunities for graduate students and postdocs today to hone their communication skills. The strategies I’ve found most effective are figuring out what topics are most relevant to people, telling stories, speaking with empathy, and truly listening to what people have to say.

pgEd has found only enthusiasm from scientists, who have been willing to participate in our meetings and congressional briefings. Some scientists, both within and outside the US, have reached out to ask how they can launch an effort similar to ours. It is inspiring that the things pgEd has learned may be useful for communities across the nation and around the world.

Recently, there is more interest in understanding the relationship between our environment and genes. Can pgEd inspire an epigenetics initiative?

pgEd defines “personal genetics” broadly so that it is inclusive of the DNA a person is born with, their microbiome, and their epigenetics. While we don’t get into the nitty-gritty of the mechanism, we find that people are often fascinated by some of the findings from these fields and where this science might go. The idea of genetic complexity is a key concept that resonates throughout all of our lesson plans.

How can trainees get involved with pgEd?

My recommendation is for trainees to visit our website and read through some of our lesson plans. We make them available online for free, so anyone can use them to bring these conversations into their local community—and please reach out to us with questions or comments. We are always interested in suggestions on how we can improve!

About the author:

![]() Faten Taki is the Liasion for the Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee and a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medical College. Her goal is to be able to give back to the scientific community while still growing as an early career scientist.

Faten Taki is the Liasion for the Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee and a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medical College. Her goal is to be able to give back to the scientific community while still growing as an early career scientist.

Learn more about the GSA’s Early Career Scientist Leadership Program.