By Daniel J. Gironda

In the Paths to Science Policy series, we talk to individuals who have a passion for science policy and are active in advocacy through their various roles and careers. The series aims to inform and guide early career scientists interested in science policy. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Policy and Advocacy Subcommittee.

Here I speak with Graça Almeida-Porada, Professor of Regenerative Medicine and Director of the Fetal Research and Therapy Program at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. In our interview, Graça and I discuss her draw to science, her current research with prenatal gene therapies, how public perception can persuade policy changes at a national level, and how young scientists can get involved in policy.

Dan: I thought we could start off with a little bit of background about yourself. Where do you come from, and how did you get into the field of stem cell research and gene therapy?

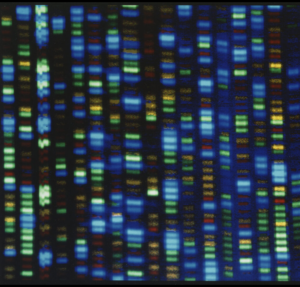

Graça: I was born and raised in Portugal. Since I was a kid, I have wanted to be a scientist because I loved to read books about the lives of scientists such as Madame Curie, Albert Einstein, and others like Florence Nightingale. They were kind of my superheroes. After finishing medical school, I did my residency, and then I completed a fellowship in hematology/transfusion medicine. I always had this dream of doing research, but in Portugal at the time (over 20 years ago), there weren’t a lot of opportunities to do research, especially for a clinician. During my last year of my fellowship in hematology, I applied for and was awarded a scholarship from the Portuguese government to come to the US to do my PhD, focusing on the impact of cytomegalovirus in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. In the lab next door, there was a pioneer in the field of in-utero hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and I absolutely fell in love with the concept. I thought that it would be absolutely the best thing in the world if you could treat someone before they were born, so they could be born healthy and have no problems afterwards. During my clinical work, I often felt that I didn’t have the tools to treat many of the benign, hematological conditions that I saw on a daily basis—there just weren’t any real solutions. I remember the kids with hemophilia—small kids that we had to poke their veins and put catheters through to give clotting factors. The current state-of-the-art medical treatments just couldn’t offer solutions to these patients. It was this realization, coupled with my desire to do research, that motivated me to come and do my PhD.

Dan: Given that your work with gene therapies is performed prenatally, there’s probably some pushback. In terms of a conversation with a policymaker or some greater institution, how would you have that conversation with someone saying that you’re playing with their genetics and that it was a higher power’s intention to give them their disease?

Graça: These are very important ethical issues to consider. I want to make it very clear that although we do gene therapy and cell therapy, we do these procedures at a time during development that is ethically acceptable. We don’t ever perform procedures during the embryonic stage; everything we do and are proposing to do is performed during the fetal stage of development, at a time when all the tissues are already patterned and developed. However, this has been a difficult point to get across not just to the general public but also to other colleagues—first, because they are not aware that these procedures are actually quite straightforward from a technical standpoint. Since all fetal therapies involve two individuals, the mother and the fetus, our first concern always has to be the well-being of the mother and her safety, and any procedure we consider cannot ever place the mother at risk.

To go back to your prior query concerning “playing a higher power” by treating these diseases before the child is born, this doesn’t seem to be an issue at all if we treat these diseases after birth. Wouldn’t it be far better to treat these diseases prior to birth and thereby enable the child to be born healthy and reach his/her full potential? As a scientist, I, of course, will always uphold the strictest ethical morals. We are trying to offer a treatment option. We’re not saying everyone should undergo this treatment. This must be the mother’s or the parents’ choice. If people want to try it, fine; if they don’t want to try it, there are other possibilities for treatment after birth. We just have to clearly and accurately communicate the potential benefits and risks to the parents, so that they can make an appropriately informed decision. As such, fetal transplantation is like everything else in science and medicine; the community needs to work together to try to develop these treatments.

Dan: And that’s the beauty of autonomy—the patient’s right to choose comes first. To shift, I think most scientist-politician relationships all begin with communication or lack thereof. How can we best illustrate the efficacy of our work?

Graça: I think that as we (scientists) transmit our results to the scientific community in meetings and conferences, it is imperative to be aware that we must translate the knowledge to the public in general and to clarify questions that the public may have. As I am sure you are aware, policy is intrinsically associated with science, because all scientific funding ultimately comes from the policymakers who allocate funding to the NIH. To create awareness in the community—not just within the general population but also within the scientific community and with the policymakers—is crucial because we can’t develop these therapies without funding. If foundations and institutions, such as the NIH, think that it’s not a good approach to treat the disease, they won’t provide funding, the field dies, and then these potentially transformative treatments never see the light of day. It is vital to appreciate that all these therapies—be they for adults, children, or even for a developing fetus—take time. So, I think policy in sciences is essential because the people in the government who are in charge of making the budget should understand that the country needs to be at the cutting edge of science and be capable of developing new technologies, not just in the field of medicine but in other scientific fields as well. To stay at the edge of innovation, money is needed. If policymakers can facilitate and promote scientific funding, that is certainly something from which the US and every other country would benefit.

Dan: How or what would you recommend for young scientists, such as myself and your students, to help minimize the distribution of misinformation, and how can people get involved?

Graça: Maybe explore alternative career paths in science policy for young people who understand the science and who have worked in a lab. These are the people who can help to bridge multiple different fields and make a huge impact. Young scientists need to be the ones driving and leading science policy and the decision-making process with the lawyers and politicians because scientists understand the science. So that would be a way of ensuring that people who truly understand the issues would be able to use media to reach large groups of people, defend science, and serve as advocates for any type of science, but especially for genetic disorders. Groups like this are essential because science policy is as important as science itself, and such groups enable scientists to help steer science policy and thereby take the future of science in their own hands.

Dan: I agree. We need a greater team effort between the scientists and the policymakers. To understand both the language of science and the language of policy helps push policymakers to actually implement those changes through active communication.

Graça: I think people should be aware that scientists spend their lives working really hard to find solutions to problems that plague humanity. Scientists don’t do things to harm people. We try to develop new tools to get us to a better place, to a healthy state, at least speaking for the people who do biomedical research. At the end of the day, people in science are always happy to speak about their work with anyone who is willing to listen, and they are just trying to make a better world for us and for future generations.