The mild temperament that distinguishes the family dog from its wolf ancestors is just one of a whole array of traits that seem to have evolved during domestication. Domestication syndrome refers to the suite of characteristics commonly observed in domestic animals, including docility, shorter muzzles, smaller teeth, smaller and floppier ears, and an altered estrous cycle. Some work has suggested that these characteristics are linked to neural crest cell deficits during embryonic development, and research featured in the August issue of G3 has revealed a possible mechanism.

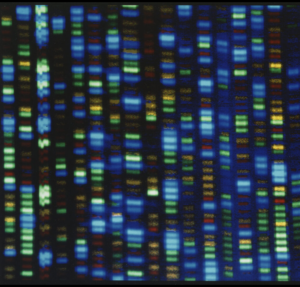

The researchers discovered that free-breeding dogs, whose mating has not been carefully managed by humans, had several genetic differences from pure-breed types of both East Asian and European origin. The dogs differed in genes involved in development, metabolism, the nervous system, and behavior—all traits affected by domestication. Prior research uncovered similar categories of genes with signatures of selection between dogs and gray wolves, implying that the comparison between free-breeding and pure-breed dogs can provide insights into the effects of artificial selection (resulting from the regulation of dog breeding by humans), whether it occurred in the very earliest or later stages of domestication.

Surprisingly, the researchers noticed that several of the affected genes are linked to each other by the Hedgehog signaling pathway, which is a major contributor to development of bones, the skull, muscles, brain, sex organs, neurons, and olfactory pathways. Perhaps most intriguingly, one of the Hedgehog genes, called Sonic Hedgehog, inhibits adhesion and migration of neural crest cells from their source, the neural tube, by providing positional cues. In vertebrates, the same gene regulates craniofacial development, a process that is strikingly different between dogs and wolves.

Further supporting the link between domestication and neural crest cell migration, the researchers found that one of the disparities between the pure-breed and free-breeding dogs occurs in a homolog of a gene known to affect neural crest cells. Another candidate gene is involved in the diseases Bardet-Biedl syndrome and McKusick-Kaufman syndrome in humans. People with Bardet-Biedl syndrome often have flattening of the midface and crowded teeth. In mice, deleting this gene disrupts Sonic Hedgehog signaling, causing defects in cranial neural crest cell migration. The end result is a shortened snout—one of the characteristics of domestication syndrome.

These findings suggest that problems with neural crest cells are central to the domestication syndrome. This could explain why dogs’ tameness is accompanied by physical differences that make dogs look distinct from wolves. It’s a two-for-one deal: good behavior and cuteness wrapped up in a single syndrome.

CITATION:

Pilot, M.; Malewski, T.; Moura, A.; Grzybowski, T.; Oleński, K.; Kamiński, S.; Fadel, F.; Alagaili, A.; Mohammed, O.; Bogdanowicz, W. Diversifying Selection Between Pure-Breed and Free-Breeding Dogs Inferred from Genome-Wide SNP Analysis.

G3, 6(8), 2285-2298.

DOI: 10.1534/g3.116.029678

http://www.g3journal.org/content/6/8/2285.long