In the Decoding Life series, we talk to geneticists with diverse career paths, tracing the many directions possible after research training. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee.

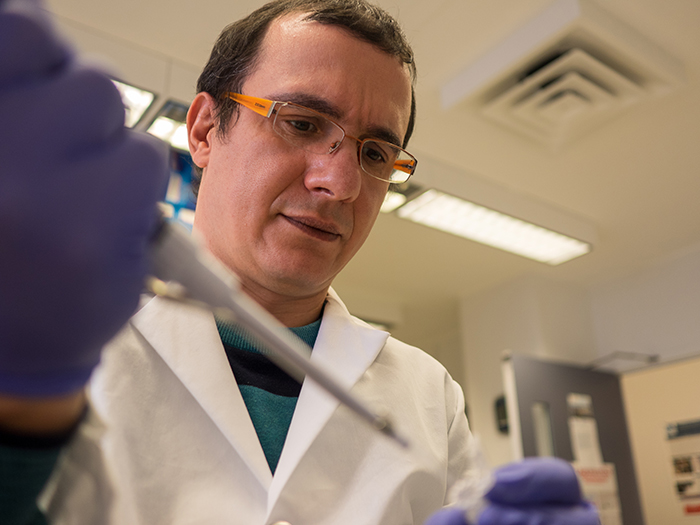

Vincenzo Alessandro Gennarino is an Assistant Professor of Genetics & Development at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. His career, which has led him from his home country of Italy to the US, is focused on understanding RNA neurobiology with a particular interest in rare diseases. He shares how his endless curiosity and passion for helping others have guided his career.

Dr. Gennarino is a first generation college graduate and an international scientist working on neurological diseases. He completed his PhD in Medical Genetics in Italy, then moved to the US to pursue his postdoctoral studies in neurogenetics. He describes himself as a person of the world who is curious about life and biology.

What compelled you to be interested in biology?

I grew up in the beautiful city of Palermo, in southern Italy. I was one of three sons. When I was very young, we didn’t have money to spend on lots of games and toys, so we used our imagination. I spent time outside, observing people, pets, farm animals, and plants. I wondered how they thought and felt about life. Then I’d go to the library and read books about anything I observed. Although I was the first in my family to go to university, my parents were very supportive of my interests and ambitions. I’m still curious today, and I think that’s what really drives me in science, along with the satisfaction that comes from asking a question and finding an answer.

Tell me about your career trajectory—what experiences led you to these positions?

I loved spending time in the library. The smell of old books still brings me back to the joy of learning. But I think things really started when my father, with a lot of sacrifices, got me my first computer. The world of internet opened up the possibility of reading science that was not in the books yet. So, I started reading about genetics and how the brain works. Then, I became interested in bioinformatics and computational biology. In 2005, I joined the lab of Elia Stupka at the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM) in Naples, where I learned about genomics and non-coding RNAs. So I pursued my PhD with Sandro Banfi, who allowed me to pursue whatever topic I wanted. At the time, it was very difficult to identify microRNA targets. I developed a new approach aimed to accurately predict miRNA target genes.

For my postdoctoral training I joined the lab of Huda Zoghbi at Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute to study neurodegenerative diseases. Since my background was in RNA biology, when I joined Huda’s Lab I didn’t know anything about the brain or mouse models. I still remember the first time I held a mouse: I thought they’re too cute to do experiments on.

In 2014, I went to my first Ataxia Investigators Meeting at the National Ataxia Foundation. During the poster session with patients, a young woman facing a lifetime of neurological degeneration asked if there was a way to cure her disease. I was deeply touched and realized how lucky I am to be healthy. I decided to dedicate my life to understanding rare neurological diseases.

In 2018, I joined the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Irving Medical Center as an Assistant Professor. I was able to meet a patient and her parents for the disease I just discovered (Pumilio1 Associated Developmental Delay and Seizures, PADDAS). The patient’s mother thanked me for all the work I was doing. That was the second time I realized I wanted to work in genetics to help patients.

Did you encounter any roadblocks during your transition from Italy to the US?

It was terrible in the beginning because I knew no English! I still remember the hours I spent on the phone trying to establish an electricity account. One trick that helped me to learn English was to not hang out with Italians. This forced me to speak English and learn by practicing.

There were lots of other roadblocks, not only about science, but about life in the US itself. I had to spend weeks without a Social Security number, so I could not open a bank account or get a cell phone contract. My wife was not allowed to work for almost a year because she did not have a work permit, which is very difficult to get. Another issue was that I could not apply for many grants without a green card. The only federal grant I could apply for, the K99, was very difficult since you must apply within 4 years of receiving the PhD.

Does the academic environment differ between Italy and the US?

They both have strengths. First, I should say that I have not been an independent scientist anywhere but here, so I really cannot compare from personal experience. But my impression is that scientists in the US have a bit more freedom to do “big science”, while scientists in Italy have to be more creative to do more with less resources.

What helped you the most in your career journey?

I think the most important thing in science is collaboration. I follow the example of Sandro and Huda in this regard. Some people don’t have the attitude of sharing their data because they are afraid someone will take advantage of them. However, I seek to collaborate and share my data even in the beginning of a project, because we can solve the puzzle faster when we work together!

When I read papers, I take note of the ones that are particularly interesting to me. Then, before I go to a meeting, I’ll email the authors I’d like to meet. Those people you meet will be the same people who will review your papers and grants most likely, and it’s easier to read a grant if you know the person who wrote it.

What is your advice to postdocs who are in the job market looking for faculty positions?

First of all, don’t be stressed and remember you are not doing this job to be rich. Be clear about why you want to be an academic scientist. With this mindset, work as much as possible to build your CV. A strong CV doesn’t mean papers in Cell, Nature, and Science, but productivity is important. The level of productivity will differ by field. A good rule of thumb is to build a second project that is independent of your main postdoc project so that if one project fails, you can still have results to build on in your own lab. This is extremely important because this is the first question people are going to ask you in your job talk. Believe me—I did 22 job talks!

About the author:

Şeyma Katrinli is a Co-chair of the Early Career Scientist Multimedia Subcommittee and a former member of the Career Development Subcommittee. She is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Emory University.

Learn more about the GSA’s Early Career Scientist Leadership Program.