Fifteen years ago, Seth Bordenstein and a small group of colleagues started planning a series of lab experiences that would bring cutting edge genetics methods into biology classrooms. Because they worked on Wolbachia microbes that live in half of the world’s arthropod species, they centered the work on these bacterial parasites and started locally with schools near their labs. Within a few years, this education project would take off beyond their wildest expectations, bringing scientists, teachers, and students together from across the United States and around the world. “It was citizen science before that term really took off,” Bordenstein says.

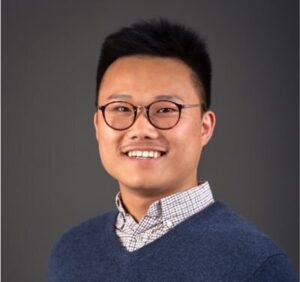

For this project, “Discover the Microbes Within! The Wolbachia Project,” Bordenstein, now Centennial Endowed Professor at Vanderbilt University, is being recognized with the 2020 Elizabeth W. Jones Award for Excellence in Education from the Genetics Society of America. The award recognizes significant impact on genetics education at any level from K-12 through graduate school and beyond.

“Not only is Dr. Bordenstein a true leader in the field of phylosymbiosis and Wolbachia-based biology, but he has also made a demonstrable impact on research-based innovative education,” says Mark Martin of the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, one of the scientists who nominated him for the award.

Although Bordenstein is being recognized alone, he notes that the Wolbachia Project is a team effort. He has acted as the project’s principal investigator, but Sarah Bordenstein now serves as project director of the worldwide program. Leveraging her experience in microbial ecology and high school science education, she has ensured that the work meets curriculum standards, has refined the project’s online components, and manages day-to-day operations with students and teachers involved year-round in the project. Other original team members were Bob Minckley, Jack Werren, and Michael Clark of the University of Rochester and educator George Wolfe of International STEM Consultants.

When the initial team formed in 2005, they planned five laboratory activities spanning the gamut of the biological sciences. The labs take students from identifying insects through DNA extraction and analysis and even bioinformatics. They reached out to their local communities, aiming to reach high school teachers or professors at primarily undergraduate institutions. They then presented an initial workshop to 24 educators, providing participants with extensive information about Wolbachia and techniques used in the experiments, such as PCR. They hoped that teachers who participated would then recruit and train others who could keep the project growing.

But the word spread faster than expected: soon teachers beyond the local communities, and even from middle schools, wanted to participate. Then in 2007, Bordenstein received a large grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) that funded the project from 2008 to 2013. “That provided a huge influx of support to scale up what we were doing,” Bordenstein says. “After 2010, it became a national and internationally known program.”

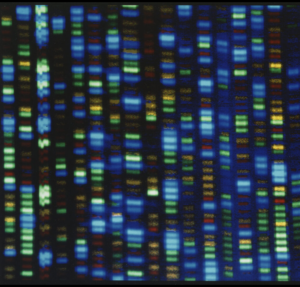

The HHMI funding also allowed the team to purchase thermocyclers that they could loan to schools, particularly in low-resource communities, and provide pipettes and expensive molecular biology reagents. When students found insects infected with Wolbachia, the team had the organisms sequenced at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and then provided the FASTA sequence files and chromatograms to the schools for free. Bob Kuhn, a science teacher at Centennial High School outside Atlanta, has noticed the confidence that the Wolbachia project has given his students. “I have had students who may not have sought out this kind of project come to me interested, and at the end of the year they have learned more than they expected.”

The lab materials are open-source and freely available online with no login requirement, so anyone around the world can use them. Bordenstein estimates that tens to hundreds of thousands of students have used the labs in some way. And some of the tools have been repurposed—translated into other languages or used in undergraduate biology courses to introduce biotechnology. Christine Girtain, a New Jersey high school teacher, has partnered with Pirchi Waksman in Israel to create a Global STEM Wolbachia Project. As a result, her students are learning far more than biotechnology, she says “My students are forging international relations and learning about team dynamics, deadlines, time management and scheduling meetings across different time zones.”

Currently the Wolbachia Project does not have dedicated funding. The work has continued in recent years through the outreach components of Bordenstein’s other grants from the National Science Foundation. If they can secure new funding, they would create more digital resources, such as new videos of experiments, provide more thermocyclers, and create a Student Center for Biotechnology information, an online data submission database analogous to the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Bordenstein hopes they can extend the original labs to facilitate a 3-foot-by-3-foot worldwide exploration challenge proposed by Bob Kuhn, where students would characterize the arthropods within a plot and screen them for Wolbachia microbes.

Bordenstein’s laboratory research on Wolbachia has flourished, too, but this educational work remains a guiding principle in his career. Bordenstein’s first major grant as an independent researcher was the HHMI science education grant, he notes. “I’m glad it was, because it gave me a sense of the bigger needs out there, the reward beyond just producing knowledge, but sharing it and implementing it with the future scholars of tomorrow.”

The Elizabeth W. Jones Award for Excellence in Education recognizes individuals or groups who have had significant, sustained impact on genetics education at any level, from K-12 through graduate school and beyond.

The next nomination period will open in September 2020.