GSA member Krista Dobi, new faculty and former Trainee Advisory Representative to the GSA Board of Directors, tells Genes to Genomes about the importance of an Individual Development Plan (IDP).

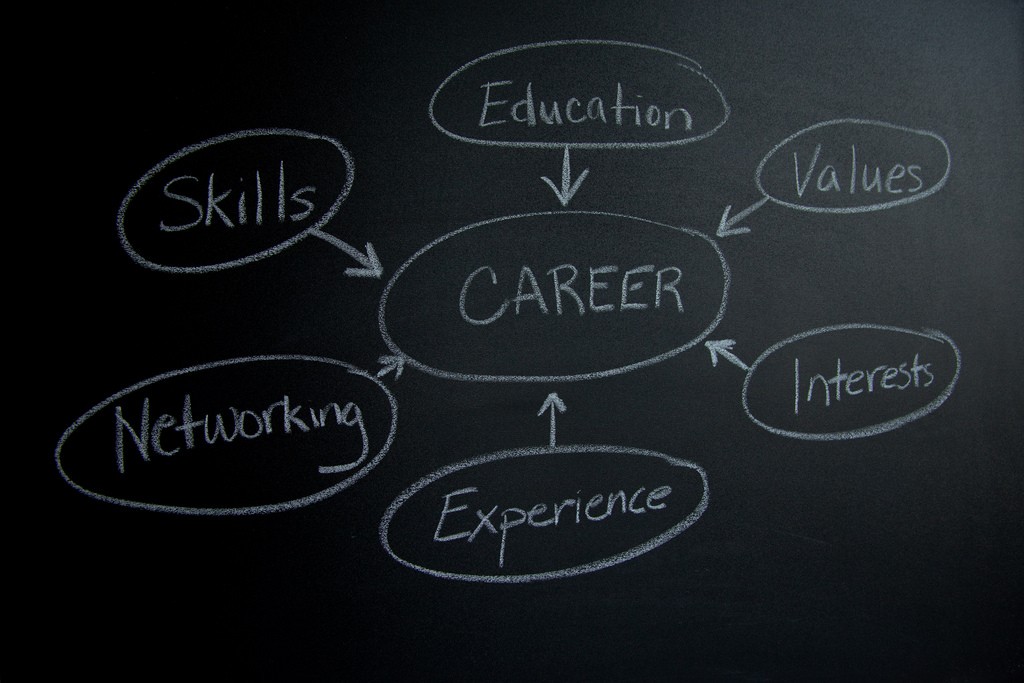

January: a time to consider resolutions for the upcoming calendar year. Since it’s the midpoint of the academic year, it’s also a great time to assess where you stand in relationship to career and professional goals. That’s where an IDP comes in.

What’s an IDP?

Don’t let the acronym fool you. Despite being used by business managers, the Individual Development Plan has been embraced by the scientific community. IDPs are being incorporated into graduate and postdoctoral training programs, and have become an integral component of some funding mechanisms (for example, NIH requires a discussion of the use of IDPs in annual progress reports for all T, F, K, R13, R25, D43 and other awards).

But the real reason to use an IDP is not to satisfy a funding requirement; IDPs are an important tool for helping you identify your strengths and weaknesses, and planning for future career success.

In essence, an IDP asks you to do three things:

1) Determine your known skills and strengths;

2) Identify skills to learn and areas for improvement; and

3) Make a plan to fill in any gaps so you’re ready for your next career step.

The IDP relies on self-assessment, but will be stronger with feedback from your mentor or advisor. Ideally, the process of assembling the IDP will be part of an ongoing conversation about your career development. Input can also come from committee members, career counselors, recent graduates, peers, alumni and others who have already moved on in their careers.

Although common in other sectors, the IDP framework for scientists was first launched by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) in 2003.

What should I include?

While it’s important to include landmarks like passing an exam, writing a paper, or submitting a grant application, it’s good to think about other skills you are—or should be—developing as part of your training. Both laboratory (molecular cloning) and technical (programming in R) skills are important to consider. And don’t forget expertise in broader skills: mentoring students, managing a project, organizing a database, giving a presentation, collaborating with a team of researchers. These skills are often more important for career success, as potential employers may expect you to come already armed with these capabilities.

Comparing your current strengths and skills to your future needs allows you to bridge the gap. For example, you could plan to attend a workshop or learn a protocol to bring you up to speed.

Do I need an IDP?

Perhaps a better question is: who doesn’t need an IDP? Whether you’re a graduate student looking to pass her qualifying exam, a postdoc transitioning to a job in the pharmaceutical industry, or a new faculty member hoping for tenure, an IDP can give you a roadmap for your next steps. If an IDP is not already an integral component of your training program, you can develop your own with the help of online resources like the interactive web tool myIDP, hosted on the Science Careers website.

The views expressed in guest posts are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Genetics Society of America.